Feedback in Action

An 'in-school' music education programme for primary teachers

Carol Timson - Programme Leader MSc in Practice Based Research, Professional Lead Foundation Subjects, Senior Lecturer in Music Education.

Abstract

My research explores the development of generalist primary teachers’ attitudes, musical understanding and practices during a one year ‘in-school’ music education professional development programme in an urban school. The programme is provided by a UK music education charity in the situated context of a whole school learning community of early career practitioners. It is characterised by: the programme handbook comprising a singing-based curriculum and related pedagogical methods; and in-service training. This article focuses on the termly ‘in-class’ visits of the programme advisory mentor and the value of dialogic, ‘in-the-moment’ enactment of action, feedback and response, which has been characterised as ‘feedback in action’. ‘Feedback in action’ co-constructs a repertoire of musical and pedagogic interventions allowing novice teachers to push performance and pedagogical boundaries by facilitating risk-taking and enquiry. This study used a case-study approach to data collection. Interim data analysis suggests that this kind of professional development experience provides a valuable form of teacher learning in music education. Teachers who receive conferred legitimacy for emergent practice from the advisory mentor can overcome lack of confidence with regard to singing and develop effective musical practice. These findings have particular implications for teacher educators and for music education in schools and higher education institutions.

Introduction

Internationally, there has been a move away from traditional ‘in-service’ training events in recent years towards a more ‘situated’ model of workplace professional development (Avalos, 2011). On Initial Teacher Education (ITE) programmes in the UK there has been a well-documented reduction of time allocation to Foundation Subjects (including music) of the National Curriculum (Furlong et al., 2000). Many primary school teachers enter the teaching profession in England feeling that although the quality of that training is high, the amount of training that they have received in relation to teaching music has been inadequate (Hallam et al., 2007).

As a music education lecturer responsible for the initial training of primary class teachers within the University of Hertfordshire, School of Education, I was particularly interested in the work of ‘The Voices Foundation’. This organisation seeks to work with teachers ‘in-school’ to achieve a level of musical skill that instils confidence and professional agency. The Voices Foundation works to address the issue of the compensatory training of generalist class teachers of music in the context of an identified deficit in confidence and skills on career entry, and the national insufficiency of primary music specialists (Rogers, Hallam and Creech, 2008). Inspired by the work of Zoltan Kodaly (Williams, 2013), The Voices proposition is that curriculum music ‘needs to provide a carefully structured progression and continuity of learning resulting in deep understanding of music and opportunities for children’s personal achievement’ (http://www.voices.org.uk/in-school/outlineofthe1-yearprogramme/ accessed 10.10.14).

In July 2013, a local urban primary school began working with The Voices Foundation on a year-long ‘whole-school’ programme of professional training. I sought to research this partnership as a process of ‘situated’ learning (Lave and Wenger, 1991) on the thinking and practice of novice teachers in the school. To become an effective teacher of music in the context of a ‘whole school training programme’ might be seen, in relation to Lave and Wenger’s theory, to be about becoming part of a ‘community of practice’. This community, involving school managers, the music co-ordinator, class teachers and pupils, would be interactively engaged in embedding a philosophy of music education practice exemplified by The Voices Foundation programme advisory teacher trainer. I sought to gain a holistic understanding (through the exploration of multiple views) of the ways in which this programme enhanced the thinking and practice of beginner teachers.

Research aims and focus

The aim of this research was to identify ways in which the development of primary generalist teachers’ attitudes, musical understanding and practices are supported through the implementation of a singing-based curriculum supported by ‘in-class’ mentoring, team-teaching, post lesson discussion and a programme handbook of related teaching and learning resources.

This article provides a more detailed account of research reported as a thought-piece in an earlier issue of LINK (Timson, 2016). It focuses on the termly ‘in-class’ mentoring visits of the programme advisory teacher to each teacher in the school. I consider the distinctive nature of this process and the value of dialogic, ‘in-the-moment’ enactment of action, feedback and response in a temporal subject such as music, which I have characterised as ‘feedback in action’. According to Thurman and Welch (2001:175), 'our voices are a primary means by which we communicate our needs, wants, thoughts, and feelings with others … self-expression with our voices is connected to the deepest, most profound sense of ‘who we are’'. Welch (2005: 245) later reinforced this view of the significance of the voice describing it as “an essential part of our human identity”. It is perhaps not surprising that for primary generalists the intimacy of 1:1 in-class mentoring in music teaching through singing might be initially regarded as challenging. I examine how this process has impacted on staff thinking and practice, considering some implications and questions for teacher education. Additional research was conducted during a continuation programme in the school in 2015-16. That phase of the research will be reported elsewhere.

Context: An ‘In-School’ programme of Professional Training

The focus primary school (a partnership school of the University of Hertfordshire) comprises a diverse cultural community with over 50 different languages spoken by pupils and staff. It attracts additional government funding, though significantly The Voices programme was financed through a national competition (for musical development) sponsored by a major national retailer. The majority of the 12 teaching staff had recently qualified or were in the initial years of teaching. The school senior management first identified music as a priority area for staff development in the Subject Audit of the Governors Report (March 2013). Most teachers had very limited initial training or personal musicianship experience. When surveyed in March 2013, staff reported an average of 3.8 out of 10 in their level of confidence to teach music (indicating very poor confidence levels) and teachers unanimously identified music as their area of greatest need in terms of staff development.

In a combined preliminary interview for this research project with the head teacher (senior manager 1) and deputy head/music co-ordinator (senior manager 2), the stated aims of the senior management team in implementing The Voices programme were clear and cohesive. Their first objective was that: ‘Everything musical would be integrated throughout the school’ (senior manager 1). They sought ‘A joint, shared experience by staff and pupils, a common foundation, a shared experience and language’ which they hoped would lead to ‘A deeper understanding by staff of the components of the music curriculum, in order that they would teach effectively’.(senior manager 2). ‘It is important that staff develop an insight into what is an appropriate singing resource for teaching and learning’ (senior manager 2).

The School might be defined as a ‘learning community’ of early career practitioners where ‘relationships of collaboration’ are expected and ‘critical practice is ongoing’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991). A shift in the school-wide culture of teaching and learning in music was the stated aim of both the school and The Voices Foundation.

Methodology and methods

I adopted a case-study approach in order to provide insight and illumination into processes of professional development in this situation (Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2007). The atypical context, particularly with regard to funding, dictates that there is no assumption the conclusions can be generalised, although they may provide interesting pointers for further research and training. The way in which my research has been informed by grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) will be developed elsewhere. The data itself has driven the direction and emergent themes of my research. I have analysed data through the prism of my own perspectives; others may deduce something different from the data. The Voices programme is the antithesis of a ‘short term-project’, having ‘sustainability’ as a key aim. I therefore adopted a longitudinal approach focusing on changes over time with prolonged on-site data collection (Newby, 2010).

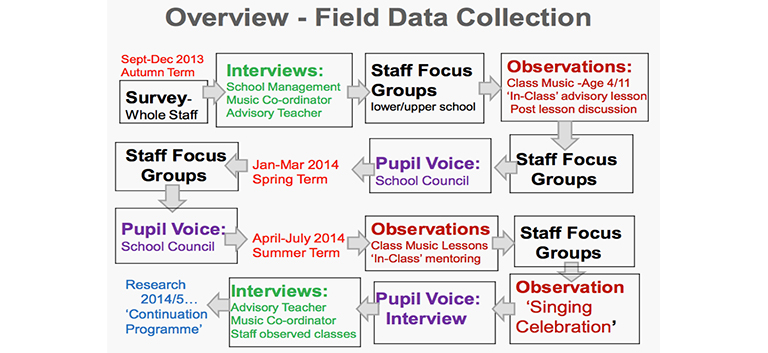

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and focus groups with 12 primary class teachers throughout the school year. Initial themes were informed by survey data. Teachers were interviewed and observed teaching in their usual working environment and during ‘in-class training’. The programme advisory teacher was interviewed and observed working collaboratively with teachers and narrative reflection and interviews conducted with the music specialist. The pupil voice, with reflections upon developing experience of musical teaching and learning, was captured through school-council discussion each half term. An overview of the data collection approaches is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 - Overview of data collection approaches

The ‘whole-school’ nature of the training necessitated the triangulation of a wide range of data sources and perspectives. These included: interviews with school management (N=2) music co-ordinator (N=1), The Voices Foundation advisory teacher (N=1) and staff from early years foundation stage to Year 6 classes (N=12).There were termly whole staff focus groups: SET 1 Lower School (EYFS to Yr 2: N=6), SET 2 KS2 (Yrs 3-6+Language Base: N=6). Pupil focus groups were held termly (pupil council meetings N=10). Observations of termly ‘in-class’ music lessons (N=8) focusing on advisory mentoring, team-teaching and post lesson discussion were key to understanding how teachers’ thinking and practice developed over time. The end of year ‘Singing Celebration’ whole school assembly was recorded and analysed for pupils’ articulation and demonstration of musical learning. Pre-existing documentary evidence, written feedback from the advisor to individual staff, programme survey data and the Curriculum Handbook ‘Inside Music’ (The Voices Foundation 2014) were analysed to offer insights into changes in teacher’s thinking and practice. Ethical considerations included gaining informed consent and preserving individual anonymity in reporting the data. Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the relevant University of Hertfordshire ethics committee.

The sequential data collection process mirrored the ‘learning journey’ of the staff and was designed to capture key points in the induction, development and culmination of the training programme. Active corroboration on data interpretation was maintained with the research participants through discussion of findings at key intervals during the programme.

Findings

Teacher Confidence: Self Perceptions of Development in Thinking and Practice

In preliminary interviews, teachers expressed substantial anxieties regarding the advisory ‘in-class’ visits, ranging from anticipation to mistrust and, in some cases, fear. For example ‘I’m anxious about the idea of in-class observation. I’ll need to put myself “out there’’!’ (Teacher 1); ‘I’m worried that children would be aware that I’m not that good’ (Teacher 3); and ‘I’m concerned about my voice …using it……that it won’t be good enough’ (Teacher 4).

The scheduled visits were initially perceived by teachers as a possible form of ‘inspection’ and personal exposure in an area of acknowledged professional and musical vulnerability: singing in public (staff survey and initial focus group).

This professional vulnerability has been well documented in the literature. As cited earlier, Thurman and Welch (2001) and Welch (2005) emphasised the importance of the voice as an essential part of our human identity and of how other people experience us. Anticipated exposure to an experienced vocal practitioner made the teachers lack of confidence more acute.

At the end of the year a post programme diagnostic survey was administered by the advisory teacher to provide an indication of how individual teachers perceived their confidence, thinking and practice had changed during the academic year. The survey utilised ‘I can do’ statements as a tool for ‘self-assessing efficacy’ against programme milestones (Gorges and Goke, 2014). During the year there was a substantial positive trend in self-grading for all teachers in relation to perceived confidence in singing and musical pedagogy, suggesting a ‘community-wide’ response.

Teachers described how they had gained confidence from being part of a school wide learning community. For example, ‘Doing it as a whole school is reassuring’ (Teacher 1) and ‘It might be something about us being a real learning community - it might not work in every school’ (Teacher 7). It seems there is something significant about being part of a community of practice, which sits well with a ‘whole school’ approach to a sustained incremental development of musical skills and understanding. In the summative ‘Singing Celebration’ teachers and pupils were communally able to demonstrate acquisition of the programme ‘milestone’ skills and to reliably and independently articulate musical concepts related to their work to each other and parents and governors.

Staff strongly identified ‘in-class’ advisory visits as the key element underlying their increased confidence - facilitating the development of their musical skills, pedagogical understanding and classroom practice. However, whilst the survey above provides an indication of changing attitudes to competencies related to training expectations of the programme, it does not capture the broader teacher learning implicit in the co-participative experience in the classroom through in-class visits. This has significance in terms of increased teacher agency and sustainability of practice and is the aspect which I will now examine further through the concept of feedback in action.

Feedback in action

The seven themes that emerged from analysing the data were informed by the data itself (interviews, focus groups with staff, the common identified aims of the school and programme advisory teacher discussed above) and by the literature (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 2000).

The themes were derived using elements of induction and deduction (Patton, 2002) and led to the identification of a single overarching concept, ‘feedback in action’, which emerged from and encompasses all seven themes. Here, feedback in action, is characterised as situated, dialogic, ‘in-the-moment’ enactment of action, feedback and response. Whilst the themes will be discussed in greater detail elsewhere, they are outlined here to contextualise the concept of feedback in action, the main focus of this article.

Theme 1. ‘Situational relevance’* of the teaching context The advisory sessions were situated ‘In-class’, with pupils, in the normal working relational context of the practitioner. The advisory teacher articulated the ‘in-class’ process as: ‘Starting from where the teacher is: what she is teaching and how she is teaching’ (advisory teacher - interview) |

Theme 2. Developing modes of co-participation –‘legitimate peripheral participation' There was a conscious strategy by the advisory teacher to develop non-threatening, co-participative modes of teaching during the ‘in-class’ visits. These were articulated as: ’Building a trust relationship…and…Working alongside a professional friend’ (advisory teacher - interview) |

Theme 3. ‘Credibility of ‘expert’: relationship and musical/pedagogical modelling The expert mentoring and apprenticeship relationship manifest in ‘in-class’ observations were layered and nuanced. It accommodated the musical understanding of individual teachers and pupils. The advisory teacher articulated the skills required as: ‘A conscious understanding of the process, in order to support & enable colleagues to enable the children’ |

Theme 4. Vulnerability of ’immigrant’ expert/ ‘conferred legitimacy’ on novice teacher A range of relational strategies were employed by the advisory teacher during the ‘in-class’ lessons. Some were implicit in the situated premise of the programme. The voluntary vulnerability of the ’immigrant’ expert into an ‘alien’ classroom secured the respect of staff and a more open response of teachers to the mentoring process. In turn, the advisory teacher was seen to confer legitimacy on the novice teacher through frequent, extemporaneous feedback ‘It has to be someone who is quite open to some of the teaching and taking over, who puts herself out … some of our pupils are quite challenging’ and ‘She made me feel like it's ok to make mistakes and not to know everything to start with’ (teacher 11 - focus group) |

Theme 5. Immediacy, risk taking and development of thinking and practice The increasing relational security fostered by informed and positive verbal feedback enabled teachers to begin to push performance and pedagogical boundaries with increased confidence. We started well, singing just to get the children’s attention, and I thought ‘I don’t know what to do next’! I kept coming across that the whole time - because she was there that really helped me. Now I don’t have to stop and think, ‘what can I do next?’ I can just think ‘well you guys keep on singing, that will give me time to work out what I need to do next’(teacher 3 - focus group) I could fly because K would catch me if I fell’ (teacher 4 - focus group) |

Theme 6. Teacher understanding, agency and sustainability Teachers felt practice was supported in a way that nurtured teacher understanding, autonomy and agency. One teacher reflecting on mentoring advice received during the mentoring session, stated: ‘When she (the advisory teacher) then comes back, she can see if we have acted on them or actually if it’s just been a ‘one off’. I find for me it makes me do them, meet the targets and want to progress and to move on from it’ (teacher 7- focus group) |

Theme 7. Social learning system: A ‘learning community’ within a ‘structured participation framework’ A shift in the school wide culture of teaching and learning in music was the stated aim of both the school and The Voices Foundation. In final focus groups teachers identified the importance of a shared professional development experience: ‘We can now discuss what we are doing…vocab, pupil progress, strategies, and songs- like any other subject!’ (teacher 8 - focus group) |

* Where sections of the headings of themes 1-7 are in quotation marks these are taken from Lave and Wenger (1991).

This concept of feedback in action emerged from the analysis of the in-class training process which gave rise to the themes in table 1. These themes capture the nature of the process: situational, co-participative, immediate and improvisational transactions between advisory expert, teacher and pupils (‘in-class’ observations of advisory sessions R-Yr 6). Staff strongly identified ‘in-class’ advisory visits as the key element underlying their increased confidence - facilitating the development of their musical skills, pedagogical understanding and classroom practice. I have characterised the process of dialogic, ‘in-the-moment’ enactment of action, feedback and response emerging from the themes above as feedback in action (Timson, 2014).

Teaching music through singing requires instantaneous teacher-pupil intervention and feedback. The observed triangular, dialogic and musical interactions between advisor, teacher and pupil enabled teachers to push performance and pedagogical boundaries and take real-time risks, knowing that they would be supported and signposted to next steps. These next steps comprised a co-constructed repertoire of musical diagnosis, intervention and modelling, the scaffolding of music pedagogy, which were assimilated in the moment by the teacher. The process of feedback in action involved a co-participative, dance-like stepping forward and back of contextual intervention and enquiry. Emergent understanding was enacted by teachers and pupils, providing ‘in-the-moment’ feedback on their learning. A safe culture for this interaction was secured by the normal working relational context of the teacher, and the ‘voluntary vulnerability’ of the expert advisor in an ‘alien’ classroom. This fostered the receptivity of novice practitioners to the training process and their own musical learning. Feedback in action, an enacted dialogue in the moment, was modelled and improvised, both musically and pedagogically, in a process that conferred professional legitimacy and teacher agency.

Intra/post lesson mentoring enabled this learning to be co-articulated, promoting ‘conscious competence’ (Whipple, 2015) and supported early career teachers’ discernment and articulation of pedagogical content knowledge (Shulman, 1987; Loughran, 2012). Interestingly, I subsequently found that what I have suggested with regard to feedback in action in a musical setting (Timson, 2014), Rizan et al. (2014) have identified in the context of clinical encounters, where immediacy is similarly a significant feature of pedagogy in practice. The spontaneous nature of musical experience ‘in the moment’ seems to lend itself to this form of professional learning. According to Swanwick (2008: 12) It is “discourse in music not about music”.

The ‘micro process’ of feedback in action between participants in the classroom was complemented by a ‘macro process’ of feedback within the school ‘learning community’, comprising teachers and pupils, and exemplified here in the Singing Celebration. Here musical knowledge and understanding was publicly enacted. In some circumstances, however, this collegiality might exacerbate the issue of professional isolation for the minority of teachers who don’t immediately ‘get it’. In such a situation, additional support strategies for professional development and self-esteem would need to be carefully considered.

Discussion and further research

Interim analysis of the data from the first stage of the research project suggests that this kind of professional development experience provides a valuable form of teacher learning in music education. An enacted dialogue ‘in the moment’, termed feedback in action, co-constructs a repertoire of musical and pedagogic interventions allowing early career teachers to challenge their own performance and pedagogical boundaries by facilitating risk taking and practice enquiry. Teachers who receive conferred legitimacy for emergent practice from the advisory mentor (De Hann and Burger, 2005) can overcome lack of confidence with regard to singing and begin to develop effective musical practice.

As a teacher educator, these initial findings, within this situational context, have notable implications for music education in primary schools and higher education institutions in the UK. Whilst there is still a place for traditional workshop-based INSET (a major part of pre-service training and The Voices programme) the findings from this research suggest that co-participative teaching supported by sustained expert ‘in-class mentoring’ is a very effective form of professional development. It appears to be particularly potent when embedded in a social learning system (Lave and Wenger (1991) (the implementation of The Voices programme) within a whole school learning community. The resource issue in the scale of investment required to support this type of situated, mentor-led teacher learning gives rise to questions of sustainability which is being addressed in future research in the continuation programme.

The examination of training processes involved in this paper may provide some illumination of teachers’ thinking and practice and begin to address the issue as to why many early career teachers feel insufficiently empowered to enact their musical/pedagogical knowledge on entry to the classroom.

Read the next thought piece...

References

- Avalos, B. (2011) Teacher Professional Development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years, 21(1), 10-20. DOI: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K. (2007) Research Methods in Education (6th Edition). London: Routledge.

- Charmaz, K. (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: SAGE.

- De Haan, E. and Burger, Y. (2005) Coaching with Colleagues: An action guide for one-to-one learning. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Furlong, J., Barton, L., Miles, S., Whiting, C., Whitty, G. (2000) Teacher Education in Transition. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Gorges J and Goke T (2015), ‘How do I know what I can do? Anticipating expectancy of success regarding novel academic tasks’ British Journal of Educational Psychology 85, 75–90 The British Psychological Society.

- Hallam, S., Burnard, P., Robertson, A., Saleh, C., Davies, V., Rogers, L. and Kokatsaki, D.

- (2007) ‘Trainee primary school teachers’ perceptions of their effectiveness in teaching music’. Paper presented at Research in Music Education, Annual Conference, University of Exeter, 10th -14th April.

- Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Loughran, J.J., Berry, A.K. and Mulhall, P.(2012) Understanding and Developing Science Teachers' Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Sense Publishers: The Netherlands.

- Newby, P. (2010) Research Methods for Education. Harlow: Pearson.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Rizan, C., Elsey C., Thomas L., Grant, A. and Monrouxe, L. (2014) ‘Feedback in Action within bedside teaching encounters: a video ethnographic study’, Medical Education, 48(9) 902-920, J. Whiley and sons. DOI: 10.1111/medu.12498.

- Rogers, L., Hallam, S., Creech, A. and Constanza, P. (2008). ‘Learning about what constitutes effective training from a pilot programme to improve music education in primary schools’, Music Education Research, 10(4), 485-497 IOE ISSN 1461-3808.

- Shulman, L. (1987). ‘Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform’. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–22.

- Swanwick K (2008). ‘The ‘good-enough’ music teacher’. British Journal of Music Education, 25, 9-22 doi: 10.1017/S0265051707007693

- Timson C (2014) ‘Examining the Thinking and Practice of Primary Teachers: A ‘In-school’ Programme of Professional Training Using a Singing Based Music Curriculum’. Paper presented at 31st ISME World Conference on Music Education, Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. 20-25th July.

- Timson, C. (2016) ‘Feedback in Action: an innovative approach to developing primary teachers’ attitudes, musical understanding and practices’, LINK 2(2) University of Hertfordshire.

- Thurman, L., & Welch, G. (2001).Body mind and voice: Foundations of voice education. Minneapolis, MN: The VoiceCare Network.

- Welch, G. (2005) ‘Singing as communication’, In D. Miell, R. Macdonald, and D.Hargreaves (eds.) Musical Communication, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Wenger, E (2000) ‘Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems’, Organization, 05/2000, 7(2), 228-242, London: SAGE.

- Whipple, K. (2015) ‘In Search of Unconscious Competence’, Legacy, National Association for Interpretation, 26(5), 30-31.

- Williams, M. (2013) Philosophical Foundations of the Kodály Approach to Education, Envoy, Fall, 40(1), 6-9.

LINK 2017, vol. 3, issue 1 / Copyright 2017 University of Hertfordshire