How we set the standard: establishing age-related expectations following curriculum change

By Jemma Coulton, research manager at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER)

In 2014, the Department for Education (DfE) introduced the new primary National Curriculum. The extent of the changes to the curriculum and assessment in primary schools was unprecedented since the National Curriculum was introduced in 1988. These changes encompassed three fundamental aspects:

In 2014, the Department for Education (DfE) introduced the new primary National Curriculum. The extent of the changes to the curriculum and assessment in primary schools was unprecedented since the National Curriculum was introduced in 1988. These changes encompassed three fundamental aspects:

- what pupils are expected to be taught, i.e. the curriculum content

- the standard pupils are expected to achieve

- the way achievement is measured, i.e. the metric or scale used, with National Curriculum levels being removed.

The removal of levels placed the onus on schools to develop their own systems of assessment to measure pupils’ attainment and progress. It is in this context that the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) began developing their second suite of reading and mathematics end of year assessments for use in Years 3, 4 and 5. Although these assessments would no longer generate levels as an outcome it was still felt that a criterion-referenced measure would be beneficial to schools. Criterion-referenced measures are those that show how well pupils are performing against a particular standard, in this case the expectations set out in the curriculum. The advantage of these types of measure over norm-referenced outcomes, which show how pupils are performing against other pupils (e.g. standardised scores), is that they allow teachers to measure pupils’ progress against specific content, i.e. the curriculum. This is especially useful in the context of curriculum reform. In the case discussed here, curriculum reform had brought uncertainty about the increased expectations at the end of Key Stage 2 and about how this would be reflected in the end of Key Stage 2 National Curriculum assessments.

Developing a criterion-referenced measure relies on standard setting, which is the process of determining what score on an assessment represents achievement of a specific standard. In this particular case, what score a pupil needed to achieve on the assessment to indicate they were working at the expected standard for their age as set out by the new curriculum.

In order to set standards on an assessment, data from large-scale trialling is combined with the professional judgement of experts, typically teachers, who consider the same assessment in the context of the curriculum. This article outlines the standard setting exercises conducted by NFER to develop the criterion-referenced measure that forms part of the NFER end of year assessments in reading and maths. It also provides theoretical background on standard setting, in particular the Bookmark method, and outlines some of the challenges encountered during the process.

Standard setting

Standard setting is defined as ‘…the process of establishing cut scores on examinations.’ (Cizek and Earnest, 2016). If you consider performance on an assessment as a scale, a cut score is the raw score on an assessment that indicates the boundary between two categories of performance, or standards, i.e. the number of marks that a person must achieve in order to fall in a certain category of performance (Cizek and Earnest, 2016).

These categories could include, for example, pass / fail, Level 3 / Level 4, grade 4 / 5, or working towards expectations / meeting expectations.

There are several standard setting methods that are widely used across multiple industries. None of the standard setting methods are necessarily ‘better’ than another but rather they each have advantages depending on the context. For example, one method may be preferable when the assessment being considered is composed of multiple choice items, or when time for the standard setting process is limited (Cizek and Earnest, 2016).

All standard setting methods require an understanding of the skills and knowledge that people who fall in each of the categories would be expected to have. For example, if the purpose was to set the cut score between grade B and grade A on an assessment, we would first need to understand exactly what grade B and grade A performance looks like. It is this understanding that underlies any judgements made (Cizek and Earnest, 2016). This process can be difficult in periods of curriculum reform or uncertainty or when the new / changed expectations are still bedding in.

In addition, some standard setting methods require understanding of a hypothetical ‘borderline’ group of test takers, i.e. a set of test takers who, in terms of performance, are just on the borderline between the two categories being considered. For these methods, the understanding of this hypothetical ‘borderline’ group is crucial as it is at this borderline between categories that we are aiming to set the cut score.

The Bookmark method

In the standard setting exercises conducted by NFER the Bookmark method was used. The fundamental basis of the Bookmark method is an ordered item booklet (OIB). This OIB contains all of the items in the assessment, organised in order of difficulty from easiest to hardest, based on difficulty determined by data from a large-scale trial. The main task in a Bookmarking exercise is for the participants to work through the OIB considering whether each item would be answered correctly by their ‘borderline’ group, i.e. their hypothetical group of pupils who are at the ‘borderline’ between the two categories of performance being considered (Cizek & Bunch, 2007). Participants continue this process until they reach a point where they believe their ‘borderline’ group of pupils would no longer have a good chance of correctly answering the question, and therefore any subsequent questions. Bookmark meetings typically include several rounds of this process which allows participants to refine their initial judgements in response to feedback. The final part of the process is to average the positions of each judge’s bookmark and this is converted into an equivalent raw score on the test. This raw score forms the cut score which represents the point at which a pupil moves between categories, for example, from ‘working towards’ to ‘achieving’ age-related expectations.

The Bookmark method has several advantages, including the relative ease of understanding the process, its ability to be applied to selected and constructed response items and the ease of setting multiple cut scores (Cizek & Bunch, 2007). However, it does require statistics on item difficulty, obtained from analysis following trialling.

Methodology

NFER conducted six standard setting meetings in order to set cut scores on their end of year 3, 4 and 5 reading and mathematics assessments. The standard setting meetings took place over two days, with the meetings on each day focussing on a different subject. The meetings for each of the three year groups took place on the same day, but involved separate groups of teachers and NFER teams. Each group contained approximately 15 teachers with over 80 teachers taking part in the whole exercise.

Understanding of curricular expectations and ‘borderline’ performance

As described earlier, the initial stage of the Bookmark process is to ensure that all participants have a shared understanding of the standard against which pupil performance on the assessment is being measured. As discussed previously, one challenge of this in the particular case of the NFER tests is that the tests were developed in the context of a new National Curriculum.

The aim of the standard setting meetings was to develop a measure which would indicate whether pupils were meeting, or indeed exceeding, age-related expectations. However, the new curriculum only indicated what pupils were expected to be taught in each year group, not their expected achievement. The Department for Education (DfE) later published performance descriptors, i.e. indicators of what pupils were expected to achieve, as part of their test development frameworks, in 2015. Even then, these descriptors only related to the end of Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2, not to individual year groups. Therefore, an initial obstacle to the Bookmark process was ensuring that researchers and teachers understood how the curriculum content could be translated into age-related expectations. To support our understanding of these expectations we referred both to the curriculum and the interim teacher assessment frameworks published in 2015 by DfE. Both of these documents were sent to the teachers before the meetings and they were asked to consider what picture these documents painted about the skills and abilities of pupils working at the expected standard, or exceeding it, alongside their own professional understanding of their pupils.

At the beginning of the meetings small group discussions were held with participants reviewing the skills and abilities of pupils at the ‘borderline’ between achieving and not achieving age-related expectations, for various aspects of the curriculum, e.g. inference, or understanding of probability. Through sharing the results of these discussions as a whole group, participants were able to arrive at a common understanding of what the hypothetical ‘borderline’ pupil, who is just within the achieving age-related expectations category, looks like in terms of performance within different areas of the curriculum.

Bookmark placement

Following discussions of the standards, teachers received an ordered item booklet (OIB) containing all of the items from the test they were considering. As outlined earlier, this places all the items in order of difficulty from easiest to hardest. In this case, the difficulty estimates were based on the results of the large-scale standardisation of the tests which took place in June 2015. This trial involved a nationally representative sample of over 1500 pupils per year group.

The role of the teachers at this point in the Bookmark process was to consider the skills needed to answer each item against their understanding of the expected standard of performance set out in the curriculum. They then placed a ‘bookmark’ (usually a post-it note) on the last item that they believed a pupil at the borderline between not achieving and achieving age-related expectations would have a good chance of answering correctly. Here a ‘good chance’ is defined as a 67 per cent or 2/3 chance of answering the question correctly.

The bookmark placements of the individual teachers (i.e. the most difficult item that individual teachers judged ‘borderline’ pupils would have a good chance of answering correctly) were collected and entered into a bespoke software program that converted the average difficulty estimates of these bookmarked items into an equivalent cut score (or raw score) on the assessment. This cut score is then intended to represent the minimum raw score that a pupil must achieve in order to be judged as achieving age-related expectations.

Normative and impact feedback

An important part of this process is the feedback teachers receive in between the several rounds of bookmark placement. This helps clarify the process and also helps develop teachers’ understanding of how their bookmark placements are converted into a raw score. Both normative and impact feedback were provided after the first round of bookmark placement. Normative feedback involved anonymously stating the lowest and highest bookmark placements in the group as well as reporting what raw score on the test corresponded to the average group bookmark placement. Impact feedback uses data from the large-scale standardisation trial and tells judges what percentage of pupils would be in the ‘achieving age-related expectations’ category if the final cut score was set at the current group average. This helps provide a real-world sense check of whether the percentage of pupils who would be categorised as achieving age-related expectations (and also therefore those not achieving age-related expectations) seems reasonable given the teachers’ professional judgement.

The results in all cases were that the initial group cut score was perceived as being too high, i.e. the raw score pupils would need to achieve to be categorised as ‘achieving age-related expectations’ was judged as too high by the majority of teachers.

This led to discussions about why viewing the items in the assessment individually might be leading to an inflated sense of what pupils working at expectations would likely achieve. Other teachers noted difficulties in consolidating their own professional judgement with the wider context of the new increased expected standard at the end of Key Stage 2 set out in the curriculum.

Following feedback, teachers returned to their OIB and began the process anew, reconsidering each item against the likely performance of a pupil at the borderline of achieving age-related expectations. Following each round, further normative and impact feedback was produced. After round 3, the final cut score was arrived upon by averaging the final bookmark placements of all the teachers taking part. It was found that in most cases the average bookmark placement decreased during rounds 2 and 3 in response to feedback.

High achievement

The next stage was to place a cut score between ‘achieving age-related expectations’ and ‘high achievement’. As the standard for high achievement is less well defined in the curriculum, identifying pupils at the borderline between these groups proved more challenging than the distinction between those achieving and not achieving age-related expectations, which is understandably more of a focus in schools. The process for setting this cut score mirrored the previous rounds.

Challenges

There were several challenges in using the Bookmark method, some of which have been outlined above. Firstly, this method has a complicated theoretical basis. For example, considering the performance of a ‘borderline’ pupil can be quite an abstract concept and can also be influenced by the range of ability that teachers are familiar with from their own classrooms. Although a consensus was arrived upon in each group as to what this ‘borderline’ pupil represented, making judgements based on subtle gradations in performance is understandably challenging.

Additionally, the statistical model which underlies the Bookmark method is complex and can be difficult to understand without delving into the wider statistical context. Some participants struggled to understand how their bookmark placements were related to the eventual cut score represented as a raw score. The statistical model behind this process is based on item response theory (IRT) which is difficult to explain clearly and helpfully in the time limits of a standard setting exercise.

Another challenge was that at the time of the standard setting exercises the curriculum was still fairly new and the wider expectations still somewhat in flux. Pupils had not yet sat the new National Curriculum assessments so some teachers were still struggling to reconcile their understanding of pupil achievement with the expectations of the new curriculum. This challenge may become less of an issue in future standard setting exercises as teachers become more familiar with the expectations of the curriculum.

Finally, possibly related to difficulties outlined above, some teachers felt that the finalised cut scores were quite high. Although teachers seemed consistently happy with their bookmark placement in relation to what ‘borderline’ pupils could do in the assessment, they had some concerns when presented with the raw score that this corresponded to. Several teachers, especially in the Year 5 groups, commented that this dissonance may be due to the change in the expected level of performance at the end of Key Stage 2 and the increased demand of the new curriculum. It was also mentioned that it is likely that the change in demand of the curriculum would mean that a significant percentage initially would not meet age-related expectations.

These high standards reflect the higher expectations set out by the DfE It is also worth noting that the impact data outlined above was based on the performance of pupils who took part in the trial who had only been taught the new National Curriculum for one year. As pupils (and teachers) become more familiar with the new curriculum it is expected that the number of pupils who fall into the ‘achieving age-related expectations’ group will increase. This may be particularly apparent in mathematics, where there were widespread changes to the content and structuring of the curriculum.

Teacher judgements

Although all participants in the standard setting exercise were experienced teachers, and could therefore draw on their professional judgement, the majority had not taken part in, nor had knowledge of, the Bookmark process. It was, therefore, valuable to gather their views on the process to inform any future exercises. Generally, the majority of teachers were happy with the information they had been given to understand the process and felt that the Bookmark method was fairly user-friendly. However, some teachers did feel that they could have benefited from further clarification about the standard setting process.

Some of the difficulties with accessing the theoretical context of standard setting are outlined above but the outcomes of the participant questionnaire seem to indicate that it is possible to give enough background and context within a single session to make the process accessible and productive.

Outcomes

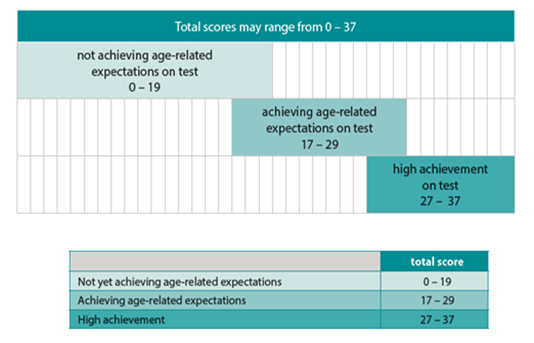

The outcome of the standard setting exercise was a set of tables, which show how performance on the NFER summer tests maps to age-related expectations based on the new National Curriculum. These tables are included in the teacher guides provided to schools with the assessments (see Figure 1). One interesting aspect of presenting the results of the exercise was the decision to provide the cut scores as a range, rather than a single score. There are several reasons for this. Most importantly, as with any outcome from these assessments, the results are designed to be considered alongside the wider evidence base for a pupil’s attainment gathered through teacher assessment. As such, when identifying whether a pupil has achieved age-related expectations or shown high achievement, the tables presented to teachers have a ‘grey area’ of several marks around each of the boundaries between categories. This is where individual teacher judgement plays an especially vital part in assessing pupil attainment. Teachers can draw on their own assessment and knowledge of a pupil’s overall day-to-day performance to determine whether they feel a pupil within this ‘grey area’ is meeting the expectations for their age, or not, or showing exceptionally high performance.

Figure 1: Tables to show age-related expectations on NFER Year 3 summer term reading tests

Conclusions

In conclusion, the standard setting meetings conducted by NFER were a useful exercise, which produced a valid criterion-referenced measure of how well pupils are performing against the National Curriculum expectations. It is hoped that this measure is beneficial to teachers and could be used alongside the other outcomes produced by the tests, in supporting teachers in understanding pupil attainment and in planning future teaching and learning. A limited survey of users found that over 90 per cent of teachers who responded, rated the age-related expectations information as ‘fairly useful’ or ‘very useful’.

There were challenges in conducting the meetings, mostly in embedding conceptual and practical understanding. However, this case study does indicate that it is possible to conduct standard setting in a time of curriculum reform, as long as sufficient time is spent ensuring participants have a shared understanding of the new or changed standard.

References

- Cizek, G.J. and Bunch, M.B. (2007). Standard Setting: A Guide to Establishing and Evaluating Performance Standards on Tests. California: Sage Publications

- Cizek, G.J. and Earnest, D. S. (2016). ‘Setting performance standards on tests’. In: Lane, S., Raymond, M.R. and Haladyna, T.M. (Eds). Handbook of Test Development, Second edn. New York: Routledge.